Are we really as happy as we make our minds up to be?

I doubt it, but I can't make up my mind.

“I am the subject of my Substack. You’d be silly to waste your time on so vain and frivolous a subject.” - Tom, inspired by Michel de Montaigne

“We’re about as happy as we make our minds up to be.” - Recovery People

Is this true? Let’s find out. I’m going to set a timer for two minutes. I’ll close my eyes and repeat “I’m as happy as I’ve ever been,” over and over until the timer goes off. Then I’ll see if I feel more happy, less happy, or about the same before and after. Here goes.

I feel a little better after the meditation, but what I mostly feel is uncertain. Two minutes isn’t enough time to know.

“I’m as happy as I’ve ever been” makes me second guess my past. Have I ever been happy? Is being as happy as I’ve ever been a low bar? In the middle of my meditation I tried a different phrase: “I can be as happy as I want.” More second guessing ensued. Is it greedy to want to be happier than whatever my resting happiness is?

I’m sympathetic to the idea of happiness being a choice or a skill, but both ideas have limitations. Circumstances have a lot to do with happiness, and choices and skills can’t overcome all circumstances. If I break my leg skiing, I will be unhappy. If someone I care about gets cancer, I’ll be unhappy. Pain makes me unhappy. Pain comes from circumstances. I don’t choose pain; pain is thrust upon me. I started writing about happiness and three paragraphs in, I’m writing about pain. What does that say.

Montaigne did something very difficult: he wrote his thoughts. Why is that so hard? Thoughts are about all anyone could write, aren’t they? No. So much of writing is imitation. Imitation is thinking like someone else. What are my thoughts versus the thoughts of others? In the jumble of everything I’ve heard or read, what do I think? “I’m about as happy as I make my mind up to be” isn’t my thought — it’s something I heard. “I’m as happy as my habits” is something else I’ve heard. I’m a behaviorist. 12 step recovery has convinced me that I can act my way into being happier, if not completely happy. Thinking doesn’t work so well.

Why do I care what other people think, like what anyone else might think when they read this? I want to be liked. Being liked makes me happy. “Should we care about the opinions of all people, or just some people?” Socrates asks in “Crito.” Just some, Crito answers. Which ones? The best ones. Who are the best ones? The dialog works its way to “we should only care about the opinions of the truly good, which might be the gods,” but Socrates doesn’t come right out and say that.

The truly good are very few. I’m likely not among them. So not only should I not care about the opinion of most people, I shouldn’t care about my own opinion. But I still want to be liked. Maybe wanting to be liked is making up my mind to be unhappy.

It’s the same old morality. “Do what’s right, and you’ll be happy.” Socrates was happy at his death. 70 was damn old for 400 BC. Socrates did what was right and was executed. Jesus did, too, and he was executed. Seems like a high bar for simple happiness, to have to die a martyr. Birthday cake is fun, too. And baseball games.

But birthday cake and baseball games are amusements, not happiness. I keep imagining someone else reading this. Will they like it? It’s not just me who wants to be liked, it’s my writing, too. Actually, the writing wants nothing. It just is. Until I delete it, and then it’s not.

Now I’m thinking that, “We’re about as happy as we make our minds up to be,” isn’t true at all. My experiment with thinking “I’m as happy as I’ve ever been,” over and over was a failure. If I can’t decide to be happy, I shouldn’t be able to decide to be unhappy, either. But I do feel like I’ve had occasions where I decided to be unhappy. Was I successful in making myself unhappy after deciding to be unhappy? I don’t have much experience to draw on. I’m generally good humored. I honestly have very little insight into my character defects. I love that phrase from recovery - character defects.

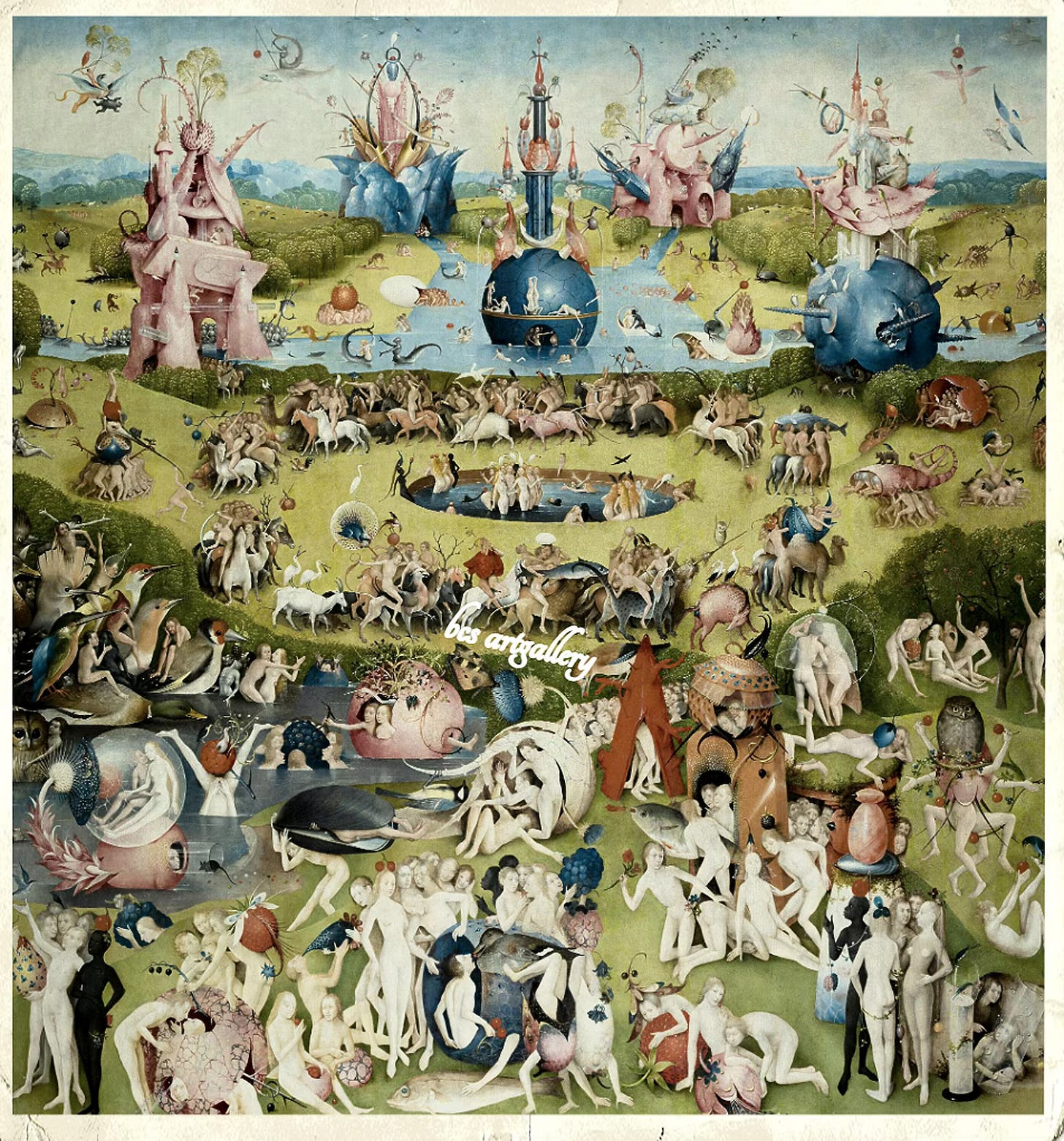

Socrates says truth is that which doesn’t change. The speed of light is truth. The relationship of a circle’s circumference to its diameter is truth. All people are mortal is truth. People value the wrong things is truth. Montaigne had a phrase that’s out of style but ever so useful - the common herd. He didn’t invent it. Arrogant aristocrats have existed for a long time. In a shameless age the ideas of shame, hierarchy, and judgment seem pretty useful. Every age is shameless. The subjects in a Hieronymus Bosch painting don’t seem a lot classier than the crowd at a NASCAR race.

“We’re about as happy as we make our minds up to be” assumes happiness is a decision, and that we know what it is we’re deciding to be. Aristotle said happiness is the reason we do everything because it’s the one thing worth having just for itself - it’s the highest good. Someone I love and respect recently told me that pursuing happiness is weak and immature. Aristotle and I disagree with this characterization of the pursuit of happiness. We’re not talking about ice cream, rainbows, and Disney World when we talk about happiness. Aristotle and I are talking something that’s worth dying for. Character. Flourishing.

For Aristotle and me, happiness is an outcome from living a good life, from being virtuous. My sister in law has pressed me to define what virtue means. I suppose it means, “Doing what God would have me do.” Bur what if there is no God? Does that mean there’s no virtue? No, I know it doesn’t mean that. I have no doubt virtue exists. Like Socrates, I can’t define it. But I’m sure it’s real.

Our actions determine our happiness in so far as our circumstances allow. Socrates died happy. Jesus might have as well, though it looks like he died in agony. Socrates chose to accept Athens verdict and dink the poison. He could have left town. His friends insisted they’d sneak him out of jail up until his last day. He chose to accept his sentence because that’s what a good Athenians was suppose to do - accept the will of the city. His happiness didn’t come from choosing suicide. It came from the practice of his virtue, part of which was to accept the will of the city.

It’s harder to say about Jesus’s state of mind at the end. If he was able to cure the sick and make the blind see, he must have been able to get off the cross. He didn’t. That was a choice. I don’t know if it made him happy, but by my earlier definition of happiness - something that’s with dying for - his choice made him ecstatic.

I started a novel. I’d like to work on it and maybe share it here. It’s sort of Republic meets The Moon is a Harsh Mistress meets Gulliver’s Travels with a lot of “tech culture sucks” thrown in.

LMK if you have interest in reading some of the book here. It would make my life easier if I can combine this Substack with progress on the novel.